*Originally published on another blog of mine, Miscellaneous Notes, now republished here with slight edits and modifications*

FEATURING — Benjamin-Franklin

A brief recap of my previous article — in Washington, DC’s Federal Triangle, a few blocks filled to the brim with, well, federal office buildings, stand two major postal facilities. One of them, the focus of said article, is the Old Post Office Building which housed the city’s main post office from 1899 to 1914, as well as the Post Office Department (POD)’s headquarters between 1899 and 1934. By 1934 most of the Federal Triangle had been built, and the POD moved across the street into the newer and more spacious “New Post Office Building,” essentially a wing of the gigantic complex now known as the William Jefferson Clinton Federal Building, or just the Clinton Building for short. I also visited it yesterday.

The Benjamin Franklin Station

Despite many renovations and additions, the New Post Office Building retains almost all of its original Classical Revival exterior, which gives it a less ornamental but arguably nobler appearance than its neighbor. In 1971, one year after the Great Postal Strike (which saw 200,000 postal workers protest low pay and seek collective bargaining rights), the Postal Reorganization Act abolished the POD, replaced it with the USPS (simultaneously demoting the unfortunate Postmaster General Winton Blount from a cushy chair in the Cabinet), and finally gave postal workers their broad, long-overdue bargaining rights. The newborn agency stayed in this building for two more years, before moving, for the 8th time in U.S. postal history, to a new home, this time the Brutalist 475 L’Enfant Plaza SW. Between 1973 and the early 1990s the building housed the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF), before being designated headquarters of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to this day.

But, just like how a small post office remains in the now-National Postal Museum building after the city’s main post office moved away in the 1990s, a small post office, named the Benjamin Franklin station, was left behind in the New Post Office Building. The station itself looked pretty regular, staffed by one single window clerk, but the corridor outside retains some remnants of the old POD.

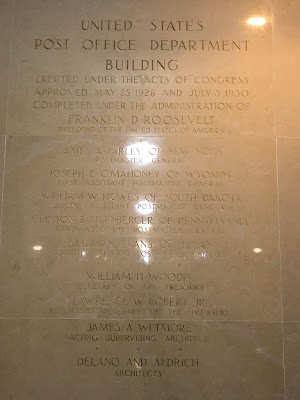

The first such remnant is an inscription in the foyer, which proudly proclaims the building’s completion “under the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt” without mentioning the poor Herbert Hoover, under whose administration the construction began in 1931. It also spelled out all four Assistant Postmasters General, the highest-ranking officers under the Postmaster General until 1949, when a Deputy Postmaster General was appointed to handle the department’s day-to-day operations so that the Postmaster General may spend more time to consider “important questions of general policy.”

The second is a series of murals and other interior decorations done between 1932 and 1938 by the Section of Fine Arts, a New Deal program managed by the Treasury to employ otherwise unemployed artists. In fact, this building was one of the first this Section worked on, as post offices were centers of community and accessible to all, hence the logical places to implement public arts.

Two pieces of arts in the foyer caught my eyes the most. One of them is the floor decor depicting two compasses and four modes of mail transportation: a steamboat, a bus, an airplane and a train car. Let’s talk about them in turn: Boats have been regularly used to transport mail in America since the early 19th century — they started out as little packet boats traveling on rivers, lakes and canals, saw extensive use during the mid-century, and grew to traverse the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans competing with their European rivals, carrying passengers as well as letters and packages.

The mail buses were a more obscure and interesting story. They were called the Highway Post Office Buses, in operation from 1941 to 1974, intended to replace railway mail. For example, one mail bus regularly traveled between Washington, DC and Harrisonburg, VA, a journey that took a little more than 5 hours, during which the in-bus clerk would have had more than enough time to sort the mail in transit.

As far as I understand, I have seen two of those buses. One of them was, of course, at the National Postal Museum, which maintains the first Highway Post Office Bus ever used. The other was at a small volunteer-run affair called the Pacific Bus Museum in Fremont, CA, which was converted into an RV after retirement. The museum’s guides proudly assured me that it was the only postal bus RV in existence, and I saw little reason to doubt the its truth.

Now we move on to airplanes, which I should not dwell too much on, as the history of U.S. airmail is well documented and easily accessible. Suffice to say that, at the time of the building’s completion, the airmail didn’t have the best of reputations — the 1934 Airmail Scandal exposed the secretive and unfair nature of the POD awarding airmail contracts to friendly carrier companies, leading to the cancellation of all such contracts and a temporary transfer of airmail duties to the Army Air Corps.

Finally, the trains — in the 1930s, more than 10,000 trains moved mail in the U.S., with clerks stationed on each to sort it en route, just like their peers on highway mail buses. However, after 1958, when the railroad companies were no longer obligated to run money-losing passenger railway lines, the number of mail-carrying trains also drastically declined, with the service’s abolition in 1977. The revival of mail-carrying trains in 1993, and how freight trains still transport mail in bulk today, are stories for another time.

The second interesting piece of art in the foyer is a colorful world map on the floor, which largely reflected international borders in the late 1930s, such as huge colonial holdings in Africa and a larger-than-now Germany. Nevertheless, the artists almost certainly took creative liberties and sacrificed some accuracy. A most jarring modification is the partition of the Soviet Union, probably in an attempt to avoid having one massive glob of color up north. There are also two typical New Deal-style murals, a few concealed telephone booths, some gilded wall decor and old-timey mail sorter desks, but they weren’t too interesting to warrant a deep dive.